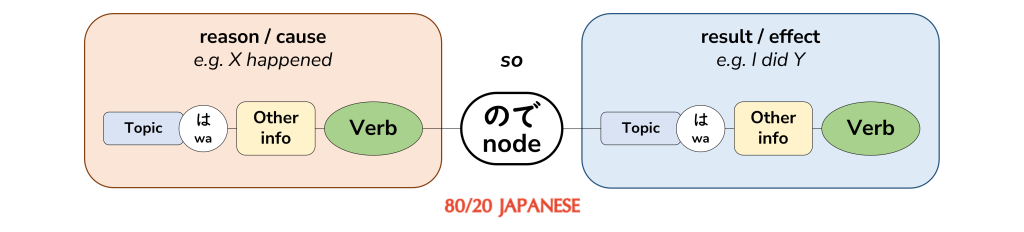

Probably the simplest way to build more complex sentences in Japanese is to take two simple sentences and join them together to form one longer sentence.

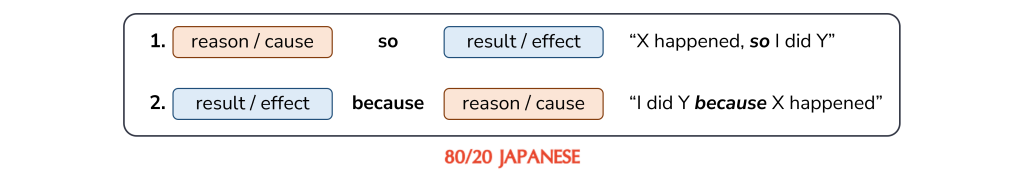

Just as in English, one of the most common situations where we would do this is when we want to explain the reason for doing something or to show cause and effect. That is, to say something like:

I did Y, because X happened.

Here, the word “because” is joining two separate statements – “I did Y” and “X happened” – and in doing so, explains that one of these actions is the reason for the other one.

Another way to express the above sentence is like this:

X happened, so I did Y.

This is the same information, but we’ve swapped the order of the statements and used “so” instead of “because”.

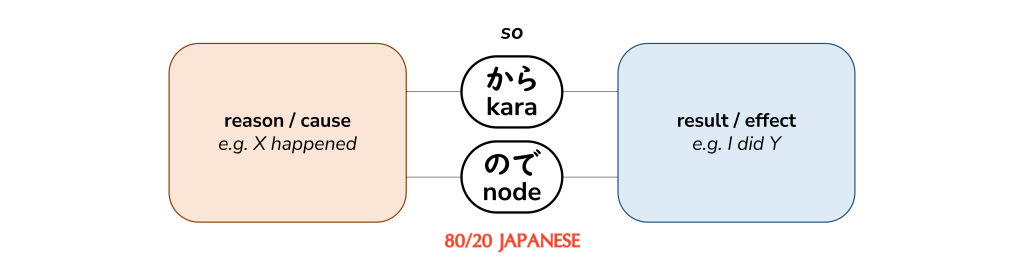

In this article, we will see how we can use the particles “kara” and “node” to connect two actions together in this way to effectively say “so” or because”.

We’re also going to do this in both polite and informal Japanese, and we will see how the rules apply slightly differently in each case.

Saying “so” and “because” in Japanese

As mentioned above, in English we can use the words “so” or “because” (or similar words like “therefore”, “since”, “hence”, etc.) to join two statements together where one of the things described is the reason or cause for the other. That looks something like this:

In Japanese, the first alternative is effectively how this is always expressed. That is, usually:

The reason or cause is described first, and the action that was taken as a result is described second.

In other words, reasons or cause and effect are typically expressed as:

X happened, so I did Y.

It is still possible to describe the resulting action first and give the reason second, but when describing both in a single sentence, the reason or cause generally comes first.

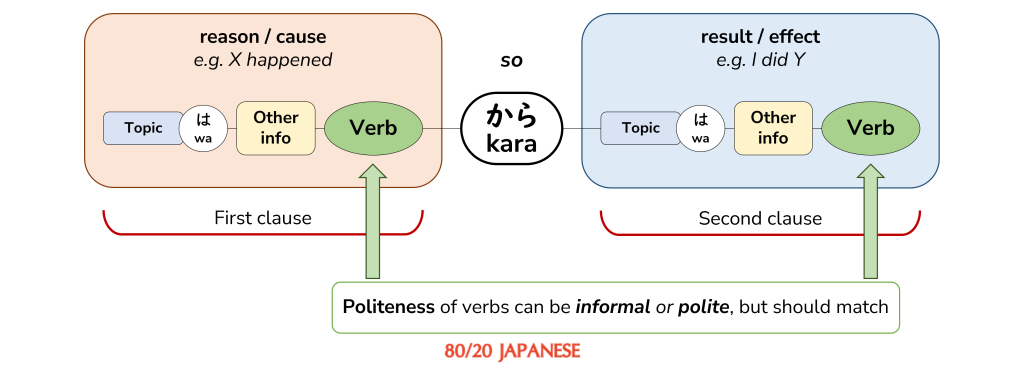

The way we express this in Japanese is to describe the reason, followed by either “kara” or “node”, and then describe the resulting action, like so:

Now, this is a very simple, high-level view of how we do this and there are some differences between the two particles, which we will look at closely in a moment.

In simple terms, the differences between using “kara” and “node” are:

- How we connect them to the first clause (the part of the sentence describing the reason or cause). The rules are a little bit different for each.

- How they work in polite vs informal Japanese. If speaking politely, “node” would generally be considered more polite than “kara”, but we can use both in either case.

Let’s take a closer look at each of these now, starting with more straightforward option: “kara”.

Using “kara” to say “so” or “because”

We can use “kara” to effectively say “so” to join a reason with its result, or a cause with its effect.

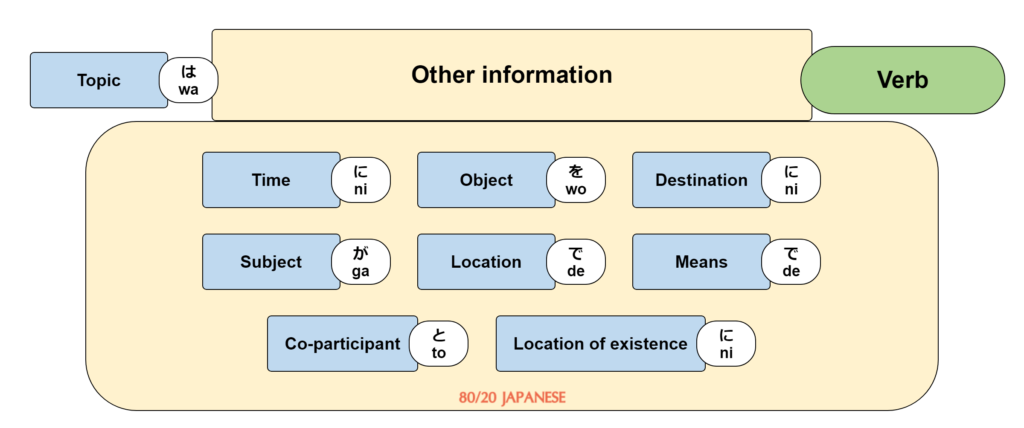

To do this, we first say our reason, and we express this in just the same way as we would express anything else according to our sentence model:

As always, we just have a topic, followed by some other information, and then the verb at the end.

Now, I usually refer to this [topic – other information – verb] structure as a model for sentences, but really, this is the structure of a clause. This is an important distinction because one sentence can have multiple clauses.

A clause is essentially one complete idea, and it always has a main verb. A clause therefore always describes at least one action, even if that action isn’t a real “action”, but is just, for example, the act of “being” as described using the special verb “desu”.

Simple sentences consist of just one clause, but if we want to say something like, “X happened, so I did Y”, we need two clauses. We need:

- One clause that says, “X happened”, then

- A second clause that says, “I did Y”, plus

- Something in between these clauses to join them together

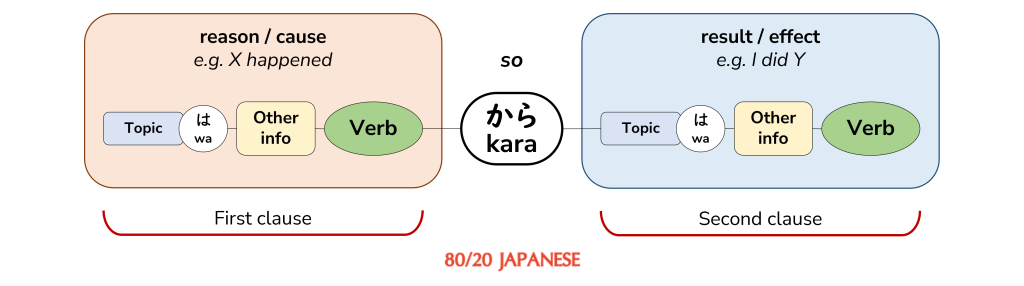

In this case, we want to use “kara” to show that the action described in the first clause is the reason or cause of the second, so it looks like this:

The way that we connect “kara” to the verb is very simple. We simple place it immediately after the verb in the first clause. We don’t need to change either clause in any way.

Even better is that we can do this with both polite and informal Japanese, so whether the verbs are in the polite form or the informal form, we can place “kara” immediately after the first clause’s verb.

That said, it is important to be consistent, so the politeness level of the two verbs should be the same.

If we want the whole sentence to be polite, then the main verb of each clause should be polite. If we are talking informally, both verbs should be informal, though it’s less of an issue if you use a polite verb in such cases.

To get a better handle on this, let’s see some examples using different types of “verbs” and different levels of politeness.

Using “kara” with an action as the reason

We’ll start with an example where we have a regular action as the reason for another action, and we’ll start by expressing it in the polite form. First, here’s the sentence we’ll use in English:

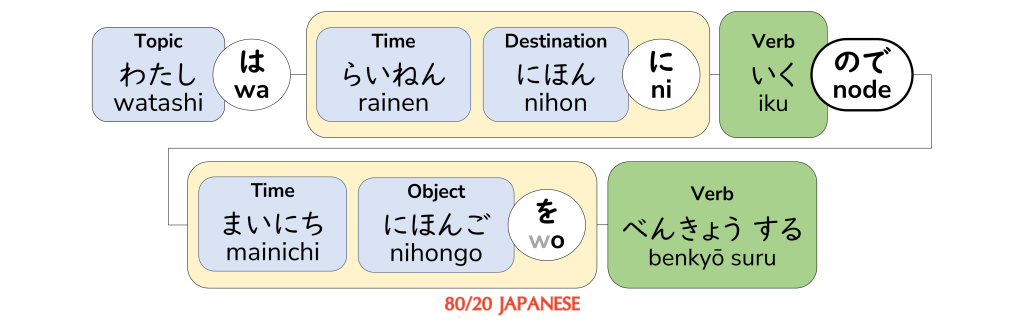

“I will go to Japan next year, so I will study Japanese every day.”

We have a reason (planned trip to Japan), and an action that is explained by that reason (will study Japanese every day), joined by the word “so”.

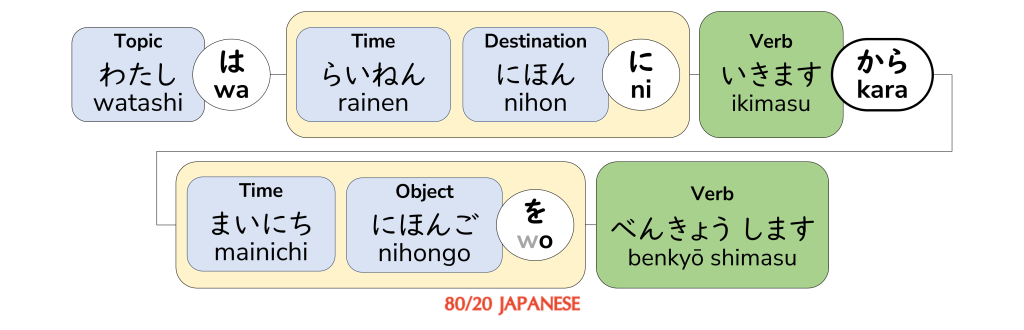

In polite Japanese, this would be:

I will go to Japan next year, so I will study Japanese every day. (Polite)

watashi wa rainen, nihon ni ikimasu kara, mainichi nihongo wo benkyō shimasu.

わたし は らいねん、 にほん に いきます から、 まいにち にほんご を べんきょう します。

私は来年、日本に行きますから、毎日日本語を勉強します。

As you can see, we first have one clause that says:

I will go to Japan next year.

watashi wa rainen, nihon ni ikimasu.

わたし は らいねん、 にほん に いきます。

私は来年、日本に行きます。

We then have “kara”, which effectively means “so,” followed by the second part of the sentence:

I will study Japanese every day.

mainichi nihongo wo benkyō shimasu.

まいにち にほんご を べんきょう します。

毎日日本語を勉強します。

Independently, the first half of the sentence and the second half of the sentence just follow the same structure of every other simple Japanese sentence.

You’ll notice, however, that while first clause has a topic, “watashi”, the second clause does not.

This is simply because it is implied. When we get to the second clause, we already know that we’re talking about “me,” so we don’t need to say “watashi wa” again.

The person who will go to Japan and the person who will study is the same person, so there’s no need to repeat this information. In English we would, but that’s because in English we’re obligated to have a subject (in this case “I”) in every clause. In Japanese, however, information that is known or understood from context can simply be omitted.

It’s also true that we don’t have to have any “other information”, either. In this case we do, but in Japanese, for a sentence to be considered complete, the only element it actually needs is a verb.

In terms of politeness, the verbs in the two clauses – “ikimasu” and “benkyō shimasu” – are both in the polite form, so of course the sentence as a whole is polite.

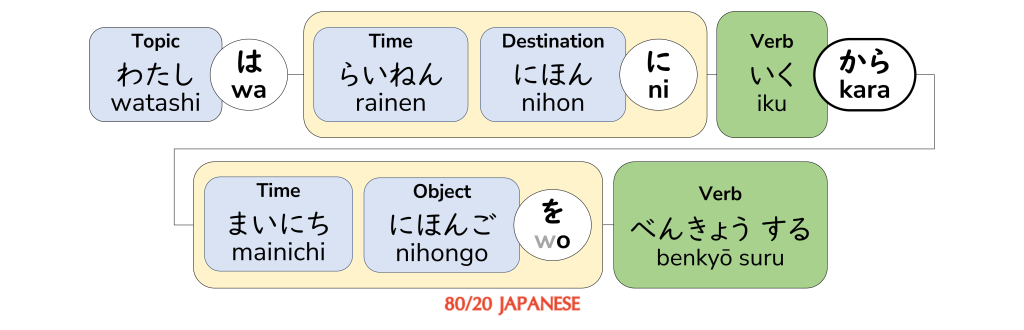

We could express the exact same thing informally by simply changing both of these verbs into the informal form: “iku” and “benkyō suru”

This sentence expressed informally would therefore be:

I will go to Japan next year, so I will study Japanese every day. (Informal)

watashi wa rainen, nihon ni iku kara, mainichi nihongo wo benkyō suru.

わたし は らいねん、 にほん に いく から、 まいにち にほんご を べんきょう する。

私は来年、日本に行くから、毎日日本語を勉強する。

All we’ve done is conjugate the verbs into the informal form, and nothing else needs to change. Whether speaking politely or informally, the way we use “kara” is the same.

Using “kara” with an i-adjective as the reason

Let’s see an example now where the reason for something is described using an i-adjective:

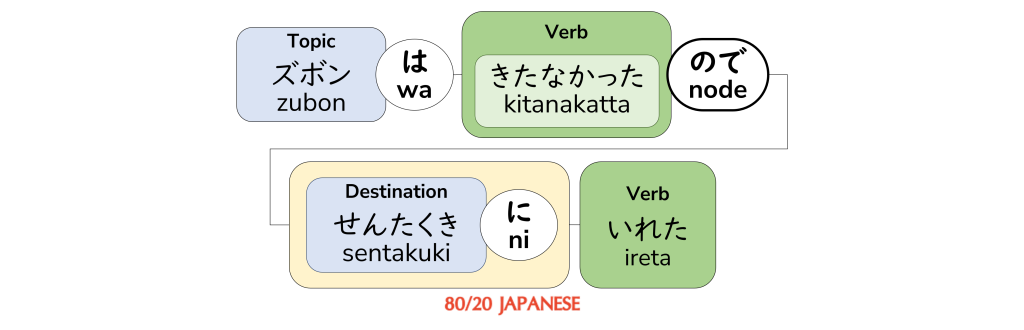

“Your pants were dirty, so I put them in the laundry machine.”

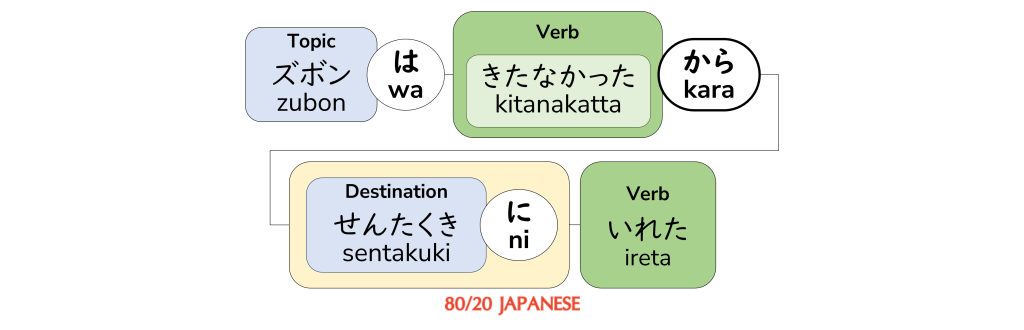

We can express this in informal Japanese like so:

The pants were dirty, so I put them in the laundry machine. (Informal)

zubon wa kitanakatta kara, sentakuki ni ireta.

ズボン は きたなかった から、 せんたくき に いれた。

ズボンは汚かったから、洗濯機に入れた。

As with the previous example, here we just have two clauses joined by “kara”.

The main structural difference here is that this time, our “verb” in our first clause is an i-adjective in the past tense. Because it’s in the informal form, we don’t add “desu” on the end; the clause just ends with the adjective.

We then join that clause to the second clause using “kara”. Of course, the second clause is also in the informal form, ending with “ireta”, which is the informal past tense form of “iremasu”, meaning “to put something in something”.

We therefore have a sentence that starts with a reason:

The pants were dirty.

zubon wa kitanakatta.

ズボン は きたなかった。

ズボンは汚かった。

Then “kara”, then the action explained by that reason:

(I) put (them) in the laundry machine.

sentakuki ni ireta.

せんたくき に いれた。

洗濯機に入れた。

We again don’t have a topic in this second clause even though the topic of the first clause (“zubon” meaning “pants”) is not the implied topic of the second clause. In the first part, we’re talking about “the pants,” and in the second part, we’re talking about “me,” who’s putting them in the washing machine. The topics don’t have to match.

How can this work? Because the context still makes it obvious that it was “I” who put the pants in the laundry machine. The topic tells us what we are talking about; it provides context. It does not necessarily describe the person doing the action.

When we say, “sentakuki ni ireta”, there is no mention of either the pants or that it is me who put them in the machine. Literally, it just means, “put (past tense) in the machine”.

That it was me who did it is implied, since there’s nobody else that I’ve mentioned, and it’s also implied that the thing I put in the machine is the pants, since that information was introduced earlier.

When we have implied information like this, in English, we fill those holes with pronouns – words like “I” and “them.”

In Japanese, we just remove those entirely, so the literal translation becomes, “the pants were dirty, so put in the washing machine.” We don’t need to include words that refer to myself and the pants because both of these are already understood, and to include them would actually sound quite redundant and silly.

The natural thing to do is to omit them and just say, “zubon wa kitanakatta kara, sentakuki ni ireta”.

Using “kara” with a na-adjective as the reason

Now let’s see an example where we use “kara” after a clause that describes a reason using a na-adjective, again in informal Japanese:

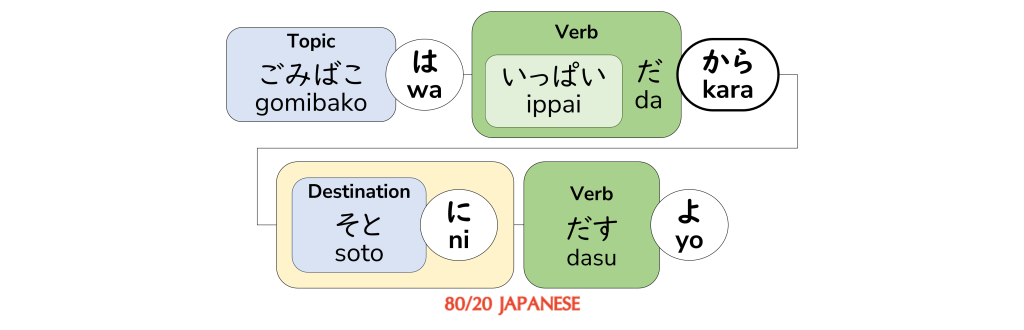

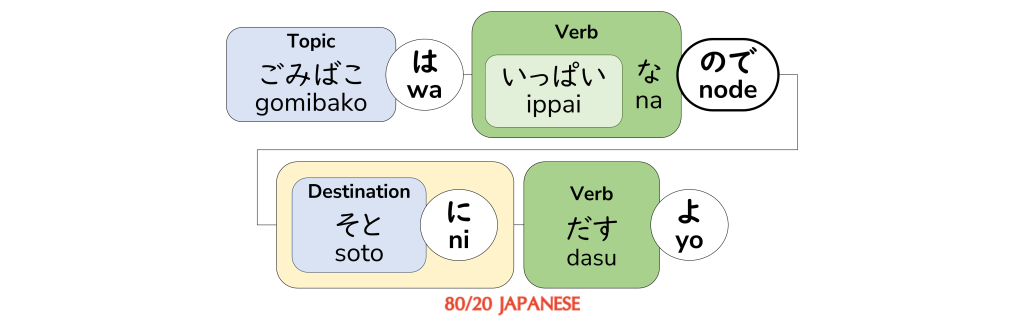

The garbage bin is full, so I will put it outside. (Informal)

gomibako wa ippai da kara, soto ni dasu yo.

ごみばこ は いっぱい だ から、 そと に だす よ。

ごみ箱はいっぱいだから、外に出すよ。

Here, our reason is described by the na-adjective “ippai”, which means “full.” The way we complete a clause ending in a na-adjective in the informal form is by adding “da”. In the polite, we would use “desu”, so the polite version of the first clause would be:

The garbage bin is full. (Polite)

gomibako wa ippai desu.

ごみばこ は いっぱい です。

ごみ箱はいっぱいです。

In the informal form, for na-adjectives like “ippai”, we use “da” instead:

The garbage bin is full. (Informal)

gomibako wa ippai da.

ごみばこ は いっぱい だ。

ごみ箱はいっぱいだ。

Then, we just add “kara” after this, followed by the second clause:

(I) will put (it) outside.

soto ni dasu yo.

そと に だす よ。

外に出すよ。

As with the other examples, we don’t need to change anything else about the sentence.

Once again, it is implied that it is “I” who will put the garbage outside, since nobody else is mentioned and we don’t have any other context.

We also know from the first part of the sentence that we’re talking about the garbage bin, so that must be the thing that I’m going to put outside.

We also have “yo” at the end of the sentence because that’s just something that some people might say in this situation, perhaps as a way to emphasize that I’m going to do this now. We’re telling the person what we’re going to do, and that’s new information to them.

As you can see from these examples, using “kara” is really quite easy. We start with a clause (which is essentially just a simple sentence) that describes the cause or reason for something, then add “kara”, and then add another clause that describes the effect or result of that cause or reason.

The two parts of the sentence are independent clauses, and we don’t need to do anything differently to them. We can use both in either the informal form or the polite form, as long as we’re consistent.

Let’s now see how we can use “node” in a similar way, but with some important differences.

Using “node” to say “so” or “because”

Just like “kara”, we can use “node” to effectively say “so”, connecting a cause or reason to an effect or result.

The order in which we structure the sentence is the same as with “kara”. We have the cause or reason first, then “node”, and then the effect or result, like so:

The big difference is in how we connect the first verb (or verb-equivalent) to “node”.

The clause before “node” is generally expressed in the informal form.

Perhaps the “plain form” is a better descriptor here, since this applies even in polite sentences (we’ll get to that soon), but we’ll stick with “informal form” for simplicity and consistency.

There is, however, an important exception:

For nouns and na-adjectives, the present/future tense form is connected to “node” using “na” instead of “da”

Let’s back up a bit.

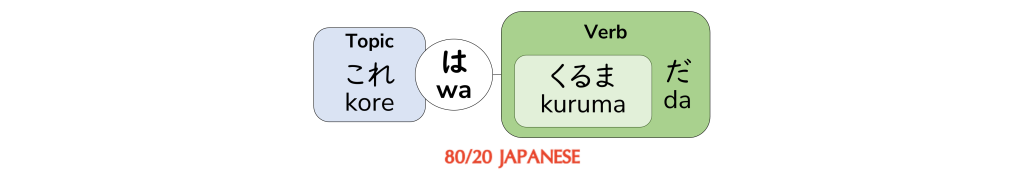

Japanese sentences (or clauses) can end either with a regular verb, or with a noun or adjective combined with some variation of “desu”. A very simple example that uses a noun and “desu” in the polite form might be:

This is a car. (Polite)

kore wa kuruma desu.

これ は くるま です。

これは車です。

In the informal form, this would be:

This is a car. (Informal)

kore wa kuruma da.

これ は くるま だ。

これは車だ。

This is in the present/future tense, because it describes what “is” in the present. If we were to express this in the past tense, we would use “was” in English, “deshita” in polite Japanese and “datta” in informal Japanese.

Now let’s return to what I said earlier:

For nouns and na-adjectives, the present/future tense form is connected to “node” using “na” instead of “da”

Our informal example above has the “verb” as “kuruma da” – that is, a noun plus “da”. We would do the same if instead of a noun, we had a na-adjective like “yūmei” (famous).

To connect a clause like this to “node”, we would change the “da” to “na”. The result would be:

This is a car, so…

kore wa kuruma na node…

これ は くるま な ので…

これは車なので…

Remember, this is the exception. For any other type of “verb”, such as a regular verb, an i-adjective, or even a noun or na-adjective in the negative form or past tense, we just use the regular informal form.

For example, if our clause just used a regular verb like “ikimasu”, we would attach “node” like so:

I will go, so…

watashi wa iku node…

わたし は いく ので…

私は行くので…

Whatever type of clause we have, once we attach “node” to the clause describing our reason or cause, we then just finish off our sentence with the clause describing the result or effect.

So, what about politeness?

With “node”, the first clause is usually expressed in the informal form, even when speaking politely.

The politeness of the sentence is therefore determined by the verb at the end of the sentence.

Unlike “kara”, the forms of the verbs in the two clauses don’t need to match. An informal verb in the first clause, followed by “node” and a second clause in the polite form would be considered a polite sentence.

In fact, a sentence where we have an informal verb with “node” and then a polite verb at the end is arguably more polite than if we use “kara” with two polite verbs.

That is to say that “node” is inherently more polite than “kara” when used in this way. The difference is quite marginal, though, so it’s not worth worrying about whether you should use one or the other.

So that we can compare them easily, let’s see our examples from earlier again, only this time using “node” instead of “kara”.

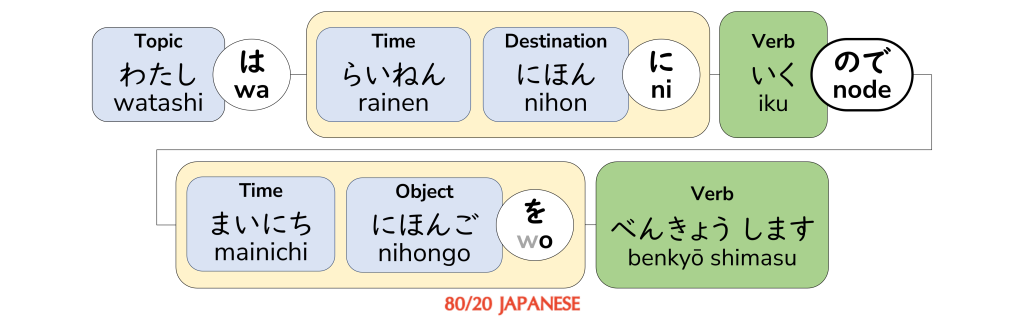

Using “node” with an action as the reason

Recall that our first example using “kara” was this:

“I will go to Japan next year, so I will study Japanese every day.“

This expressed in polite Japanese using “node” instead of “kara” looks like this:

I will go to Japan next year, so I will study Japanese every day. (Polite)

watashi wa rainen, nihon ni iku node, mainichi nihongo wo benkyō shimasu.

わたし は らいねん、 にほん に いく ので、 まいにち にほんご を べんきょう します。

私は来年、日本に行くので、毎日日本語を勉強します。

Notice that the verb at the end of this sentence is in the polite form: “benkyō shimasu”. That means that the whole sentence is polite, even though the verb in the first clause, “iku” is in the informal form.

If we wanted to change the whole sentence to the informal form, we would simply change that last verb to “benkyō suru”, like so:

I will go to Japan next year, so I will study Japanese every day. (Informal)

watashi wa rainen, nihon ni iku node, mainichi nihongo wo benkyō suru.

わたし は らいねん、 にほん に いく ので、 まいにち にほんご を べんきょう する。

私は来年、日本に行くので、毎日日本語を勉強する。

Just like that, we can change the politeness level of the whole sentence just by changing the last verb. The verb from the first clause that connects to “node” – in this case, “iku” – is in the informal form regardless.

Using “node” with an i-adjective as the reason

The next example we had was:

“The pants were dirty, so I put them in the laundry machine.”

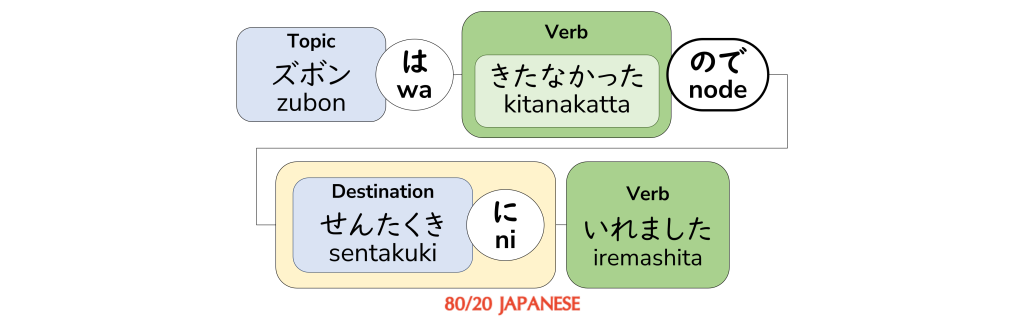

To say this informally using “node”, we might say:

The pants were dirty, so I put them in the laundry machine. (Informal)

zubon wa kitanakatta node, sentakuki ni ireta.

ズボン は きたなかった ので、 せんたくき に いれた。

ズボンは汚かったので、洗濯機に入れた。

This is, of course, in the informal form because the last verb in the sentence is “ireta”, which is the informal past tense form of “iremasu”.

The first clause ends with the i-adjective, “kitanai”, in the informal past tense:

The pants were dirty. (Informal)

zubon wa kitanakatta.

ズボン は きたなかった。

ズボンは汚かった。

Now, as we’ve said, even if we wanted to express this whole sentence in the polite form, we wouldn’t need to change “kitanakatta” to the polite form. We would not need to add “desu”.

All we would need to do make this polite is change the last verb of the sentence to the polite form, which would give us:

The pants were dirty, so I put them in the laundry machine. (Polite)

zubon wa kitanakatta node, sentakuki ni iremashita.

ズボン は きたなかった ので、 せんたくき に いれました。

ズボンは汚かったので、洗濯機に入れました。

Just as before, the way we connect an i-adjective to “node” is to just use it in the informal form. The form of the last verb then determines the politeness of the whole sentence.

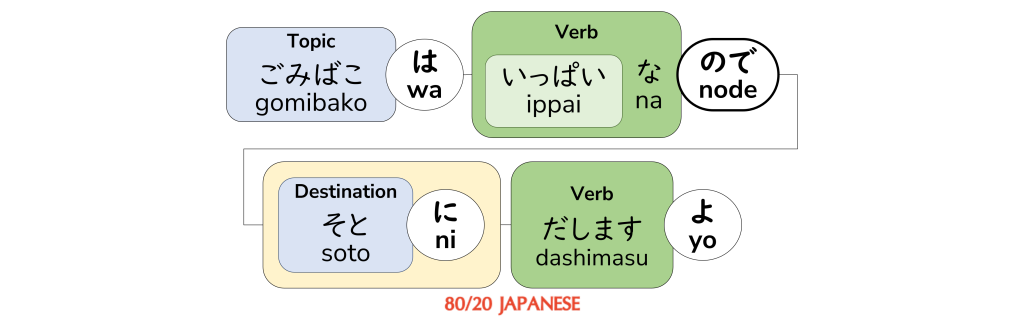

Using “node” with a na-adjective as the reason

Our next example is one where we need to be a little bit more careful, and that’s because our “verb” in the first clause contains a na-adjective.

As we said, that means we need to change the “da” from a normal informal present/future tense clause to “na”.

The sentence we had was:

“The garbage bin is full, so I will put it outside.”

To express this informally using “node”, we would say:

The garbage bin is full, so I will put it outside. (Informal)

gomibako wa ippai na node, soto ni dasu yo.

ごみばこ は いっぱい な ので、 そと に だす よ。

ごみ箱はいっぱいなので、外に出すよ。

The word, “ippai”, which means “full,” is a na-adjective (even though it ends in “i”), so if we were to just say the first part of this sentence by itself, we would say:

The garbage bin is full. (Informal)

gomibako wa ippai da.

ごみばこ は いっぱい だ。

ごみ箱はいっぱいだ。

However, here we’re connecting it to “node”, so we need to change the “da” to “na”:

The garbage bin is full, so…

gomibako wa ippai na node…

ごみばこ は いっぱい な ので…

ごみ箱はいっぱいなので…

For the second part of the sentence, we then have:

(I) will put it outside. (Informal)

soto ni dasu yo.

そと に だす よ。

外に出すよ。

This is in the informal form as it uses the word “dasu”, which is the informal form of the verb “dashimasu”, meaning “to put out” or “to take out.”

Since this last verb is in the informal form, that means that the whole sentence is informal.

Of course, if we want to express this sentence using polite Japanese, all we need to do is change that last verb, “dasu”, to the polite form, “dashimasu”. That would give us:

The garbage bin is full, so I will put it outside. (Polite)

gomibako wa ippai na node, soto ni dashimasu yo.

ごみばこ は いっぱい な ので、 そと に だします よ。

ごみ箱はいっぱいなので、外に出しますよ。

Once again, we use “ippai na node” in the first clause. The first part of the sentence is the same whether we’re speaking informally or politely.

As you can see, the way we structure a sentence using “node” is very similar to when we use “kara”, but we need to treat the verb in the first clause differently, in two ways:

- The “verb” part of the sentence is usually in the informal form, even in polite sentences

- When the first clause, when expressed by itself in the informal form, would usually end with [noun + da] or [na-adjective + da], we connect it to “node” by replacing “da” with “na”

Key Takeaways

We can join two statements (or clauses) together, where one statement is the cause or reason for the other, using the particles “kara” and “node”.

In both cases, the clause describing the reason or cause usually comes first, followed by “kara” or “node”, which is then followed by the clause describing the result or effect, like so:

When using “kara”, the main verb in each clause can be polite or informal, but they should match.

When using “node”:

- The verb in the first clause is usually in the informal form, even when speaking politely.

- In clauses that, when expressed on their own in the informal form, have a verb that consists of a [noun + da] or [na-adjective + da], the “da” should be changed to “na”.

- The politeness of the sentence as a whole is determined by the politeness of the verb at the end of the sentence.

本当にありがとうございます。素晴らしい説明でした。

Thank you so much and thank you for such a clear and detailed explanation. Now I can see the difference and similarities between から and ので.