The particles “kara” and “made” can be used to define the beginning and end of a range in either time or space. That is, they effectively mean “from” and “until”.

In this article, we will take a closer look at these two particles to see how we can use them correctly in sentences, and when it is appropriate to do so. We’ll also see how they both sometimes overlap with the particle “ni”, as well as one way they can be used that is different from other major particles.

The particle “kara”

The particle “kara” defines the starting point or origin of an action in either time or space.

Most of the time, it can simply be translated to English as “from“.

When it’s used together with a time phrase, then “kara” tells us the time when an action begins. For example, if we say “kyō kara”, that means “from today”.

If we use “kara” with a location or a place, then it tells us the location where an action involving movement begins. For example, if we said “gakkō kara”「学校から」, that would mean “from school”.

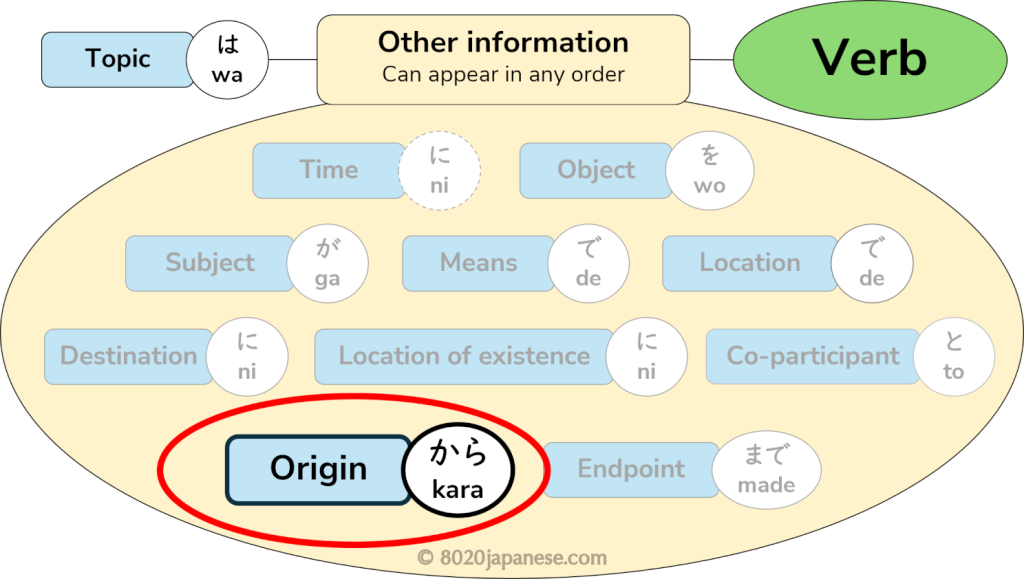

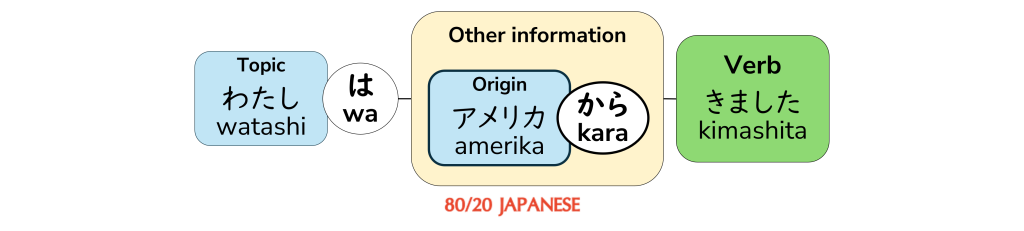

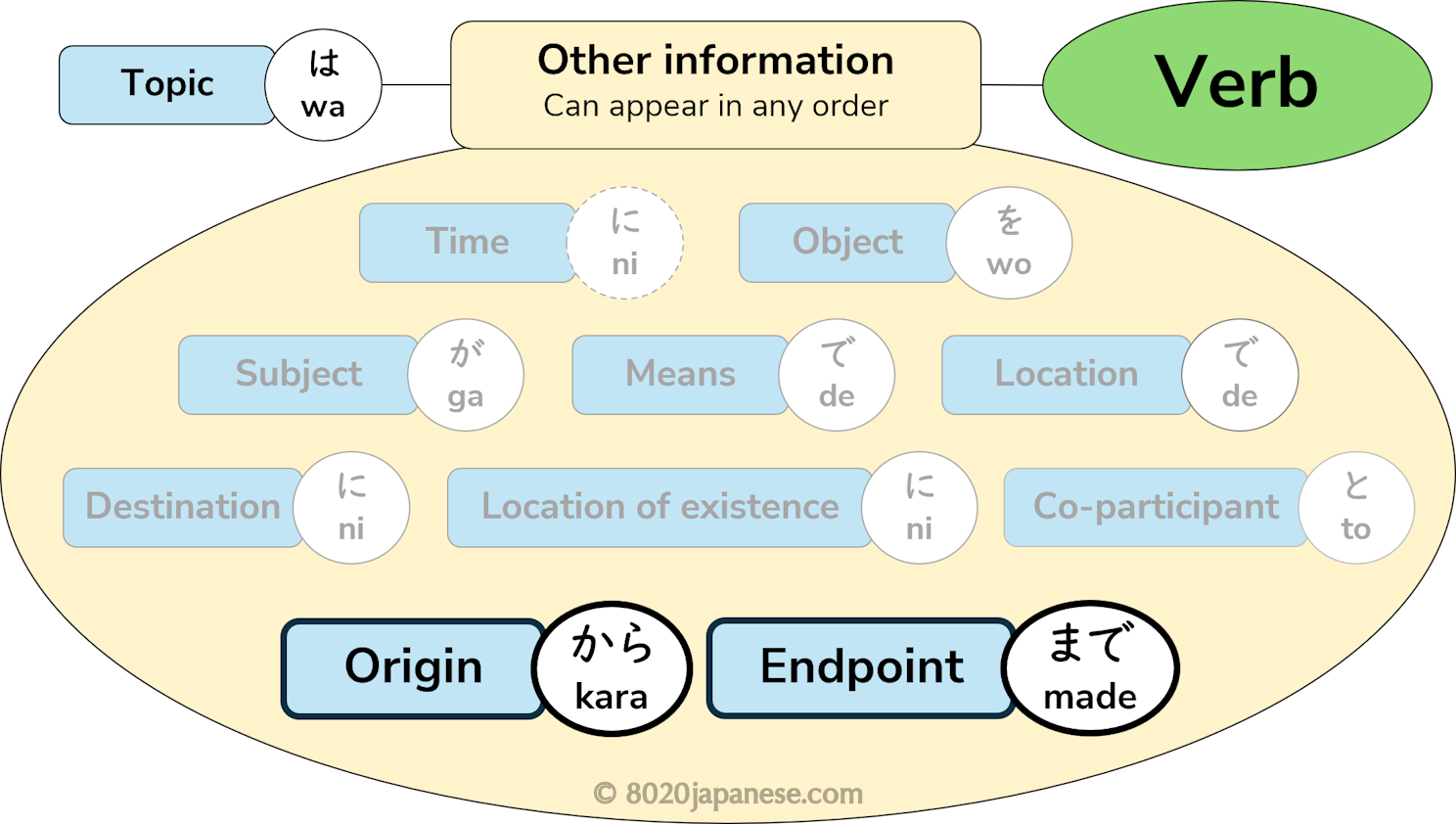

When we use “kara” in a sentence, we typically put it inside the other information section of our sentence model:

Note that the particle “kara” does have some other uses, so you will see it appear in other places in a sentence. For this article, however, we’re focusing on using “kara” to mark a starting point or origin.

Using “kara” to describe the time when something begins

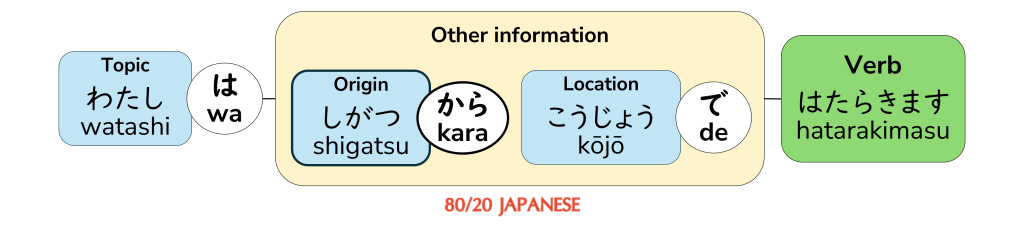

Here is an example of the particle “kara”「から」 being used in a sentence to mark the time when something will begin.

I will work in a factory from April.

watashi wa shigatsu kara kōjyō de hatarakimasu.

わたし は しがつ から こうじょう で はたらきます。

私は4月から工場で働きます。

In this example, we have “shigatsu kara”「4月から」, which means, “from April”. Quite simply, that tells us the time when the action, in this case “hatarakimasu”, will begin.

There really isn’t any difference between saying “from April” in English and “shigatsu kara”「4月から」 in Japanese. Particularly when it relates to time, “kara”「から」 essentially just means “from”.

One particularly common time phrase that “kara” is often used together with is “ima”, meaning “now”.

The resulting phrase, “ima kara”, literally means “from now”, and this is often used when talking about things that are about to happen in the immediate future, or perhaps that we are just starting now in this very moment. For example:

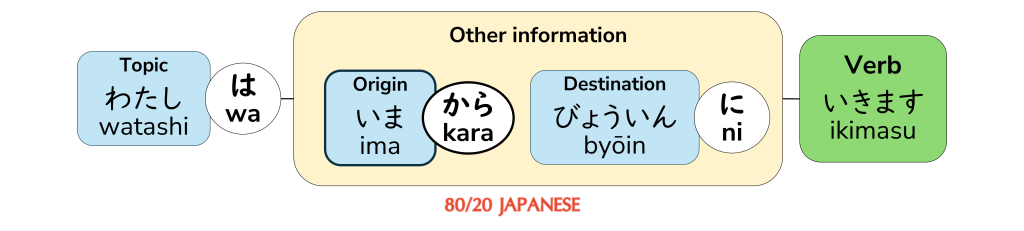

I will go to the hospital (from) now.

watashi wa ima kara byōin ni ikimasu.

わたし は いま から びょういん に いきます。

私は今から病院に行きます。

Here, we are talking about an action that I am about to take – an action that is starting “from” now.

Of course, in English, we probably wouldn’t say “from”. Instead, we would likely just use “now” by itself and say, “I will go to the doctor’s clinic now”.

To be clear, we can do the same in Japanese too. For example, we could just say, “watashi wa ima byōin ni ikimasu”. This essentially means the same thing, but it usually sounds more natural to include “kara”, even though saying “from” might sound redundant in English.

If anything, the difference between saying, “ima kara”, and just saying “ima”, is that by saying, “ima kara”, we’re making it clear that the action hasn’t started yet – that it is not an ongoing thing, but one that’s about to start now.

One reason for this difference might be that in English, if we say, “I will do it now,” or “I am going to do it now”, the words “will” or “am going to” makes it very clear that the action hasn’t started yet.

The Japanese verb forms kind of imply the same thing, but it’s not necessarily as clear, so that might be why it’s more common to say “ima kara” in Japanese, whereas in English, we would typically just say “now”.

In any case, “ima kara” is a very common expression you will hear when someone describes what they are about to do.

Interchangeability with “ni”

This point about “ima kara” having effectively the same meaning as just “ima” extends further.

What we’re really saying is that “kara” is a kind of optional addition to a simple time phrase, where its inclusion emphasizes that something will happen “starting from” a particular point in time.

This is true not just for “ima”, but for any timing phrase, including those typically marked by the particle “ni”. Consider this example:

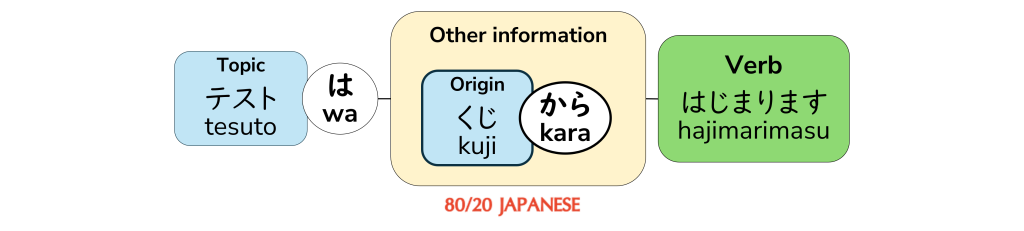

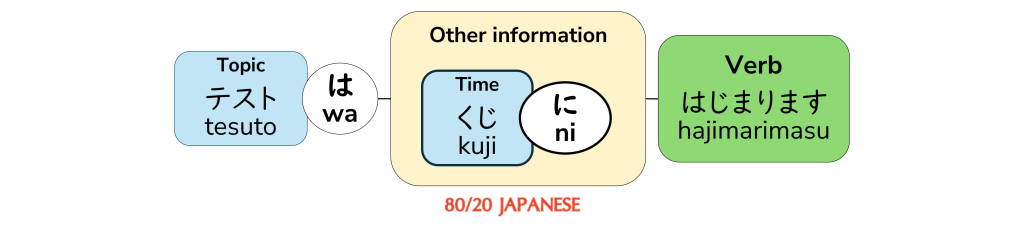

The test will start from 9:00.

tesuto wa kuji kara hajimarimasu.

テスト は くじ から はじまります。

テストは9時から始まります。

Here we have “kuji kara”, which means “from 9 o’clock”. That’s the time from which the test starts.

However, another, arguably simpler way to say this would be:

The test will start at 9 o’clock.

tesuto wa kuji ni hajimarimasu.

テスト は くじ に はじまります。

テストは9時に始まります。

The only difference between these two sentences is that the first one uses “kara” and the second one uses “ni”. Even so, just as the English translations imply, the basic information being conveyed is essentially the same.

So, in many situations, we can say either “kara” or “ni” to describe the time at which something begins. In this way (and this way only!), these two particles are somewhat interchangeable.

That said, the nuance is slighly different, with “kara” slightly emphasizing that it is the starting time.

Remember, while the particle “ni” is more general and used to describe when something takes place, the entire purpose of “kara” is to describe when something begins, so of course that is slightly more emphasized when using “kara” instead of “ni”.

In many cases, however, they convey much the same information.

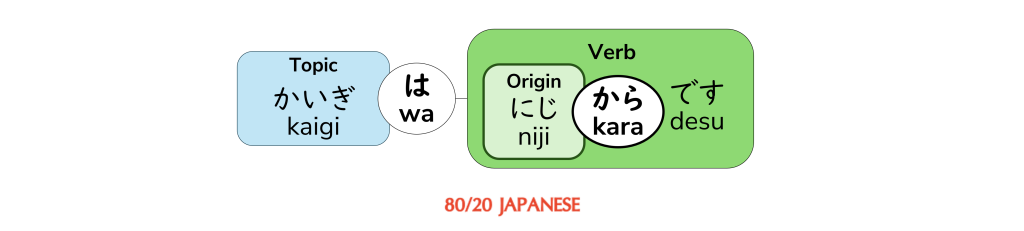

Using “kara” together with “desu”

One area where “kara” is definitely different to “ni”, however, is that, unlike “ni”, we can use “kara” immediately before the special verb “desu”.

Here’s an example:

The meeting is from 2 o’clock.

kaigi wa niji kara desu.

かいぎ は にじ から です。

会議は2時からです。

Here, rather than saying when the meeting “starts”, we’re saying when the meeting “is from”. This might not be as natural in English, but it’s quite natural in Japanese, and because it is more efficient, it’s probably more common than using a word like “hajimarimasu”, meaning “start”.

Importantly, however, we cannot use “ni” together with “desu” in the same way. When we use the particle “ni” together with a time phrase, it needs to be in relation to an action, which “desu” by itself is not.

So, although “ni” and “kara” can sometimes both be used to describe when something takes place, if we want to say when something “is from”, we need to use “kara”.

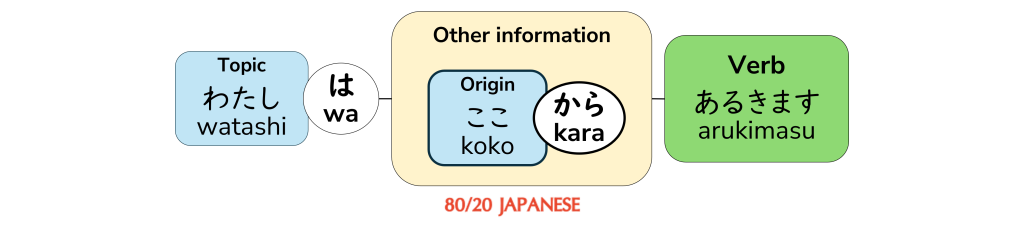

Using “kara” to describe the location where something begins

In addition to using “kara” to mark the time when something begins, we can also use it to describe the location where something begins. Here’s an example:

I will walk from here.

watashi wa koko kara arukimasu.

わたし は ここ から あるきます。

私はここから歩きます。

Just as we saw with time phrases, when we use “kara” together with a location such as “koko”, meaning “here”, it tells us where the action begins. Essentially, it can be used to mark the starting point of an action in either time or space.

One difference with locations, however, is that we can’t easily swap this with another particle like “ni”. When used in relation to space, the particle “ni” tells us the destination, which we might also call the “endpoint”, not the origin or starting point, so using “ni” in place of “kara” to mark a location would change the meaning completely.

The only way to describe the physical starting point – the origin from where an action begins – is to use “kara”.

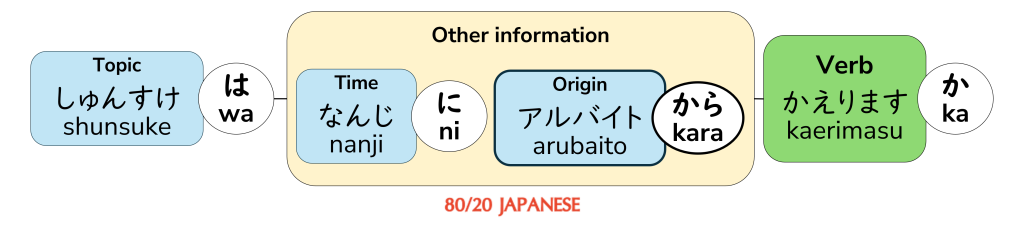

Here’s another example:

What time will Shunsuke return home from his part-time job?

shunsuke wa nanji ni arubaito kara kaerimasu ka?

しゅんすけ は なんじ に アルバイト から かえります か?

しゅんすけは何時にアルバイトから帰りますか?

Again, the particle “kara” tells us the place where this action originates from. In this case, that origin is Shunsuke’s part-time job, “arubaito”.

Notice that in the previous example, the origin was close to us, and we were going away from that origin, whereas in this case, the origin is far away, and the direction of the action will be towards us.

This shows that it doesn’t really matter where the origin is in relation to ourselves. It could be close to us, or far away, and the direction of travel could be going away from us, towards us, or in a completely different direction. In all cases, the location where the action originates from can be marked with the particle “kara”.

Here’s one more example that can helpful when doing a self-introduction.

I came from America.

watashi wa amerika kara kimashita.

わたし は アメリカ から きました。

私はアメリカから来ました。

This is one way that we can tell people where we are originally from. In English, we would more likely say something like, “I am from <insert country>”, but in Japanese, saying, “~ kara kimashita”, to effectively say, “I came from ~”, is the more natural expression.

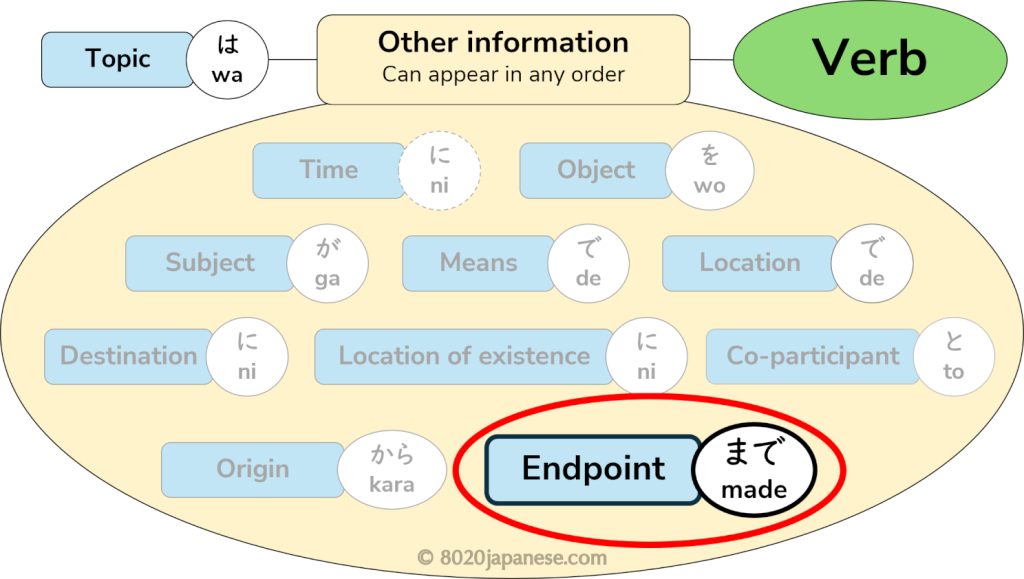

The particle “made”

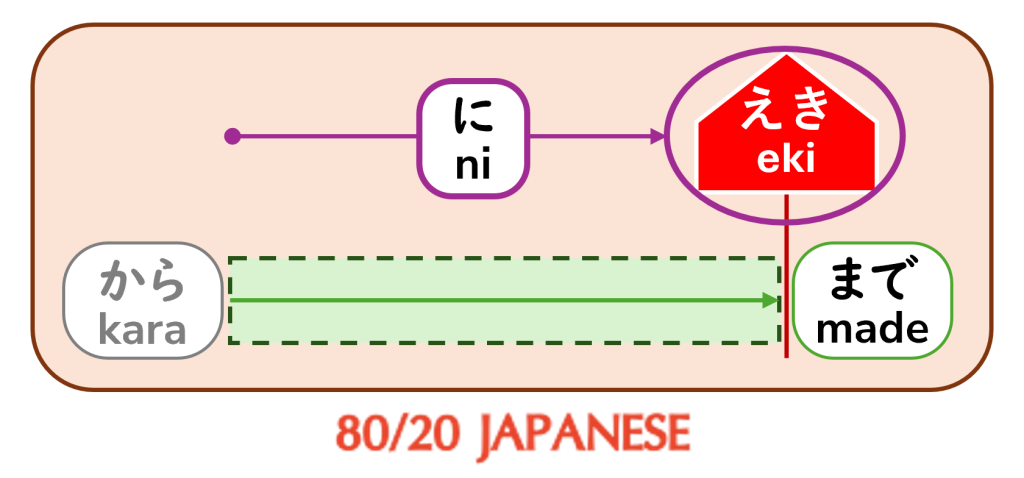

The natural complement to “kara” is the particle “made”.

The particle “made” defines the end-point of an action in either time or space.

In other words, “made” tells the time or place where an action ends.

Whereas “kara” tells us when or where an action begins, “made” tells us when or where an action ends.

When used with a time phrase, “made” tells us the time when something ends and is usually best translated as “until”.

For example, if we say, “ashita made”, that would mean “until tomorrow”.

When used with a location, “made” tells us the location where an action involving movement ends, and although it can also be translated to English as “until”, the better transation is usually “to”.

For example, if we say, “eki made”, that would mean “until the station” or “to the staion”. (We’ll see how this compares with the particle “ni” shortly.)

In both cases, as with “kara”, we would typically use “made” inside the other information section of our sentence model:

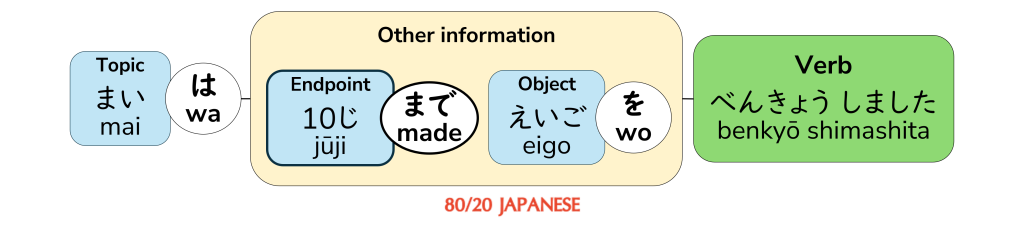

Using “made” to say when an action ends

Here is an example of the particle “made” being used to define the time when something ends:

Mai studied English until 10 o’clock.

mai wa jyūji made eigo wo benkyō shimashita.

まい は じゅうじ まで えいご を べんきょう しました。

まいは10時まで英語を勉強しました。

Here we have “jūji made”. 「10時」 means “10 o’clock”, and that is the time until which Mai studied. In other words, in terms of time, that’s the endpoint of her study. We mark that with the particle “made”.

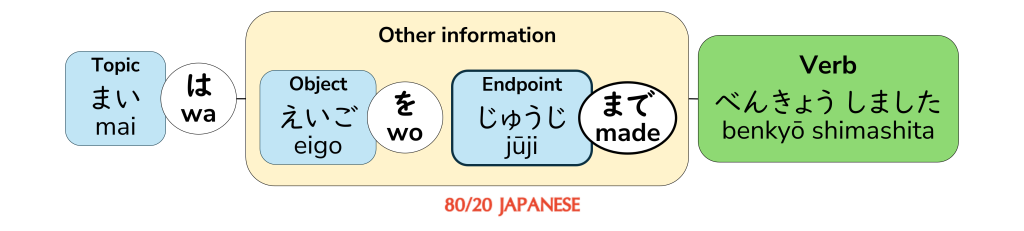

As with all “other information” elements, we can also change the order and put “eigo wo” before “jūji made”「10時まで」, like so:

Mai studied English until 10 o’clock.

mai wa eigo wo jyūji made benkyō shimashita.

まい は えいご を じゅうじ まで べんきょう しました。

まいは英語を10時まで勉強しました。

Since information that appears later in a sentence tends to carry more weight, this puts a bit more emphasis on the time until which she studied, though the fundamental meaning of the sentence is the same.

Note, too, that we could have re-arranged some of the example sentences with “kara” in the same way. In general, the elements in the “other information” section can be put in any order as long as the correct particles are used. That said, just because we can, doesn’t mean we always should.

Here’s another example:

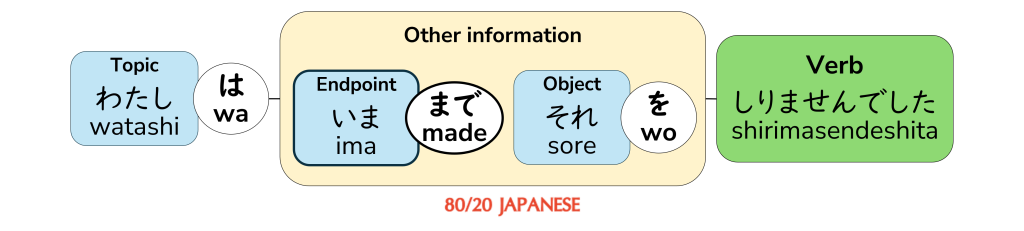

I didn’t know that until now.

watashi wa ima made sore wo shirimasendeshita.

わたし は いま まで それ を しりませんでした。

私は今までそれを知りませんでした。

Here, “ima made”, of course, means “until now”, and this is often used to essentially say, “before”.

In isolation, “ima made” describes the entire history of the universe up until this very moment, which in English, we often say using the word “before”.

In Japanese, this is more commonly expressed by saying, “ima made”, “until now”, but we could also translate this sentence as, “I didn’t know that before.”

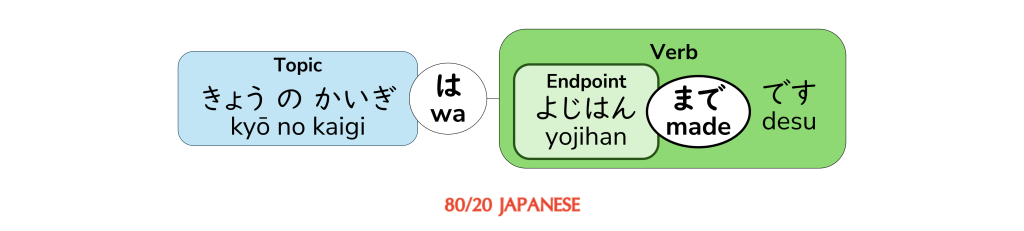

Using “made” together with “desu”

Another way in which “made” is very similar to “kara” is that “made” can also be used immediately before “desu”. For example, we can use it to say something like:

Today’s meeting is until 4:30.

kyō no kaigi wa yojihan made desu.

きょう の かいぎ は よじはん まで です。

今日の会議は4時半までです。

Here, we’re essentially saying what time the meeting ends, but without using a verb that actually means “ends”. That is, instead of saying, “today’s meeting ends at 4:30”, we are just saying that the meeting is until 4:30.

So, just like “kara”, and unlike many other particles, we can use “made” immediately before “desu” to describe the time when something ends.

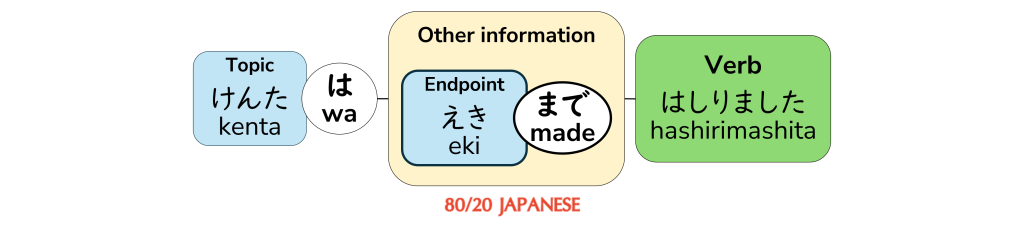

Using “made” to say where an action involving movement ends

The particle “made” can also be used with a location to define the endpoint of an action involving movement. For example:

Kenta ran until/to the station.

kenta wa eki made hashirimashita.

けんた は えき まで はしりました。

けんたは駅まで走りました。

Here, “made” tells us that the station is the endpoint of Kenta’s running. We can translate this to English as “until”, but the more natural preposition to use in English is usually “to”.

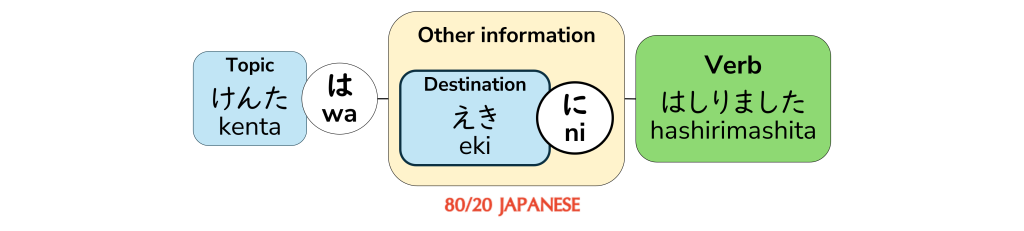

Comparing “made” with “ni”

Just like “to” and “until” can have similar meanings in English, when “made” is used to mark a location as an endpoint, the meaning is often very similar to the particle “ni”. That is, it’s often used to mark what is effectively the destination of the action.

For example, we could re-phrase the above example to instead say:

Kenta ran to the station.

kenta wa eki ni hashirimashita.

けんた は えき に はしりました。

けんたは駅に走りました。

The difference is this:

- The particle “ni” tells us that the specified location is the final destination of the action.

- The particle “made” defines one end of a range or area within which the action takes place.

The sentence, “kenta wa eki made hashirimashita”, is therefore telling us that Kenta ran until he got to the station.

He may have kept going after that, and his final destination might have been somewhere else, but he ran through the area between his starting point and the station.

It’s a little bit like saying that that’s as far as he ran – “Kenta ran as far as the station”.

So, “made” and “ni” can often both be used to say the same thing, but “made” really emphasizes the location is the endpoint of the action, not necessarily the destination.

For that reason, it tends to work better with words like “hashirimasu”, meaning “to run”, or “arukimasu”, meaning “to walk” – words that describe the way in which movement happens, as opposed to just going or coming.

However, that’s not to say we can’t use “made” with verbs like “ikimasu” meaning “go”, or “kimasu” meaning “come”. We can. We’ll see an example of that in a moment.

Using “kara” and “made” together

As you have probably assumed, it is possible, and also very common, to use “kara” and “made” together in the same sentence. The result is that we effectively define the two endpoints of a range, whether that be in time or space.

All we do is just use them in the same way as when we use them individually.

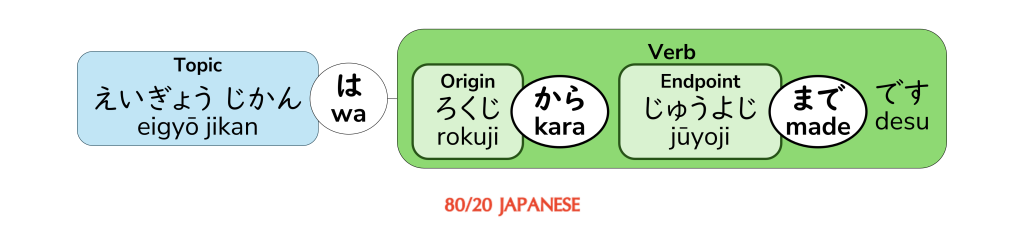

Here’s an example where we use “kara” and “made” together to define a span of time:

Opening hours are from 6 o’clock until 14 o’clock (2PM).

eigyōjikan wa rokuji kara jyūyoji made desu.

えいぎょうじかん は ろくじ から じゅうよじ まで です。

営業時間は6時から14時までです。

This is fairly straightforward. When we want to refer to a specific period of time, we can just use “kara” and “made” to mark the start time and the end time of that period.

In this example, we have times of the day:

from 6:00 until 14:00

rokuji kara jyūyoji made

ろくじ から じゅうよじ まで

6時から14時まで

(Note: 24-hour time is commonly used in Japan, even when spoken).

Of course, we can also use it with other time phrases as well. It could be “from Monday to Friday” or “from July to September”, or even from one specific date to another specific date.

Basically, with time phrases, “kara” and “made” work very much like “from and until”.

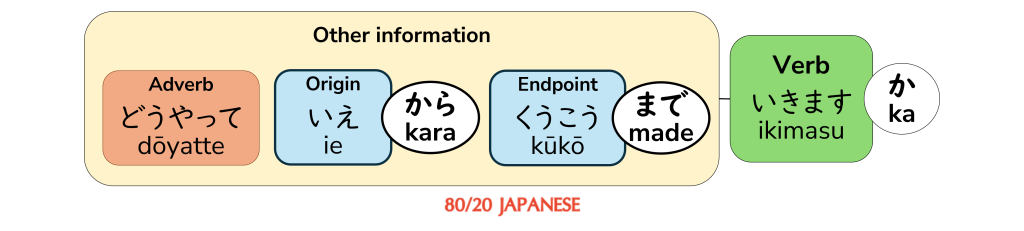

Now here’s an example of “kara” and “made” being used together to define a range or area in space:

How will you get from home to the airport?

dōyatte ie kara kūkō made ikimasu ka?

どうやって いえ から くうこう まで いきます か?

どうやって家から空港まで行きますか?

As you can see, we have both “kara” to define the origin, and “made” to define the endpoint. This really highlights that we’re describing a range or an area.

We’re then asking how the person is going to go from one end of that area to the other. This is a situation where a word like “ikimasu”, meaning “go”, makes perfect sense, even if it’s not as commonly used together with “made”.

Now, we could use “ni” instead of “made” if we wanted to. The reason we might prefer “made”, however, is because we know that the airport is not our final destination; it’s just one of the stops along the way.

Usually, we’re going to take a plane from the airport to our final destination, so this question is asking, “how are you going to do a certain part of that trip – from home until the airport?” That’s not the whole journey, and the airport is not the final destination.

We’re asking specifically about the range between home and the airport:

ie kara kūkō made

いえ から くうこう まで

家から空港まで

Since both “kara” and “made” essentially define the two endpoints of a range, they’re best suited to focusing on one particular segment of a journey, particularly when used together.

To be clear, we’re not limited to only using “kara” and “made” when referring to just part of a journey. We can also use it if that’s the whole trip.

However, in such cases, since we would be defining the final destination, then unless we have a reason to emphasize the endpoint of the action, it is typically more appropriate to use “ni” rather than “made”.

Key Takeaways

The particles “kara” and “made” can effectively be used to mean “from” and “until” in both time and space.

Tha particle “kara”:

- Defines the time when something begins

- Defines the location where an action involving movement begins

The particle “made”:

- Defines the time when an action ends

- Defined the location where an action involving movement ends

Both “kara” and “made”:

- Are somewhat interchangeable with the particle “ni” in certain cases, albeit with a slightly different nuance. Specifically:

- When saying when an action starts – 「2時から」 means “from 2 o’clock”, while 「2時に」 means “at 2 o’clock”

- When saying where an action involving movement ends – 「駅まで」 means “until the station”, while 「駅に」 means “to the station”.

- Can also be used immediately before 「です」 (unlike many other particles) to say when something “is from” or “is until”

Very good explanation about these two particles.

Thanks for sharing.

Thanks Eli! Glad you found it helpful 🙂

These materials give a great help for the Japanese learners.