There is an elegant simplicity to Japanese verbs.

In many languages, learning verb conjugations is a nightmare involving endless lists of exceptions that simply need to be memorized.

But in Japanese, verb conjugations are incredibly logical and predictable.

Especially compared to English, where many verbs have seemingly random conjugations (eat/ate, go/went, be/was), Japanese verbs follow consistent, reliable patterns. Even the few exceptions that do exist mostly follow the same patterns as all other verbs.

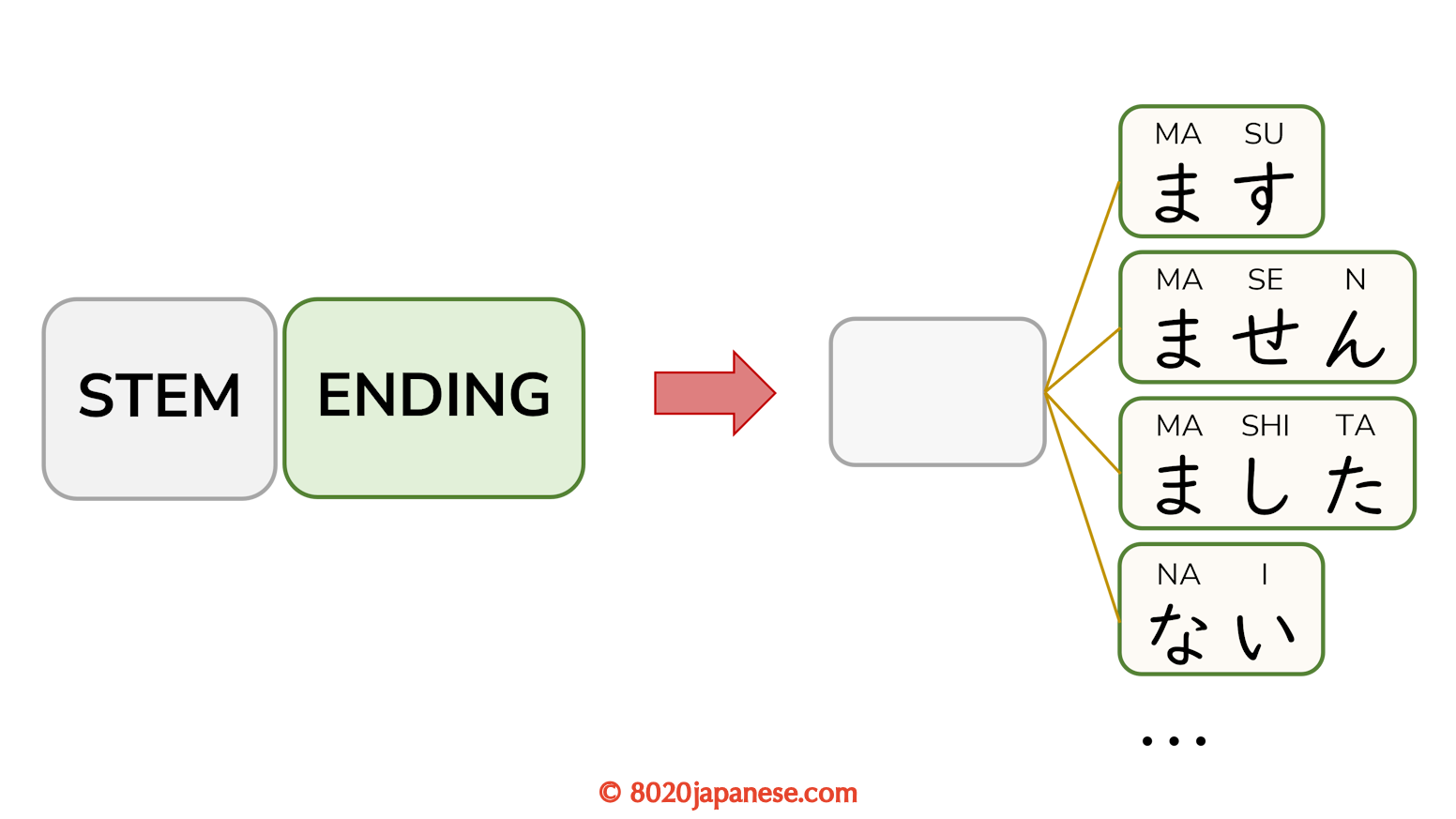

What makes Japanese verbs so logical is that they all have the same structure. Once you understand this basic structure, learning new verb tenses and forms becomes easy.

The Two-Part Structure of Japanese Verbs

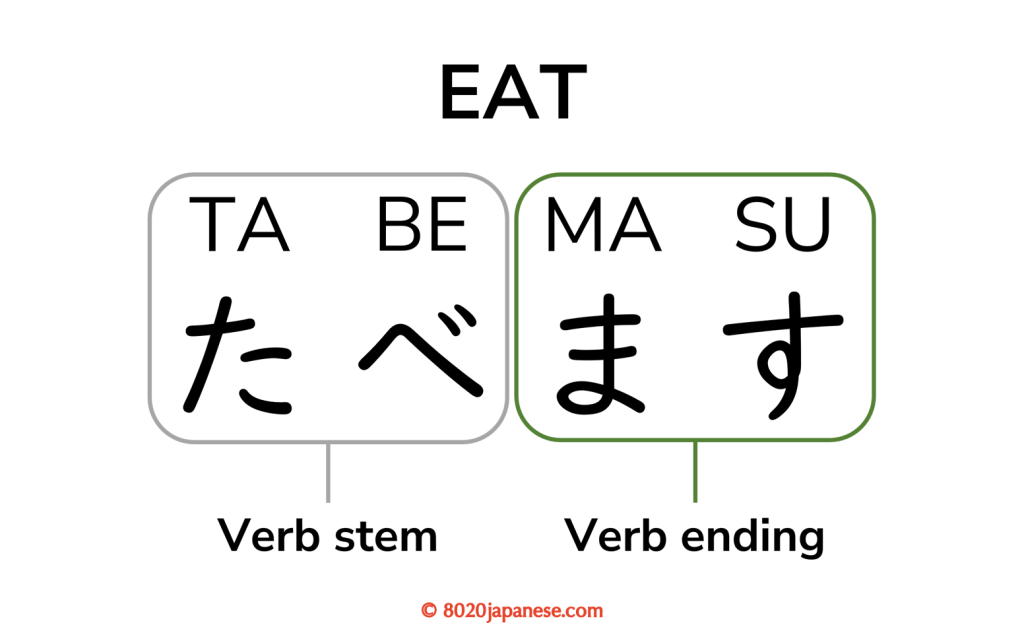

Let’s look at how Japanese verbs work as a system. We’ll use the verb meaning “eat” as our example: “tabemasu”.

Every Japanese verb consists of two parts:

The Verb Stem

The verb stem tells us what action is being described. For “eat,” the stem is “tabe”. This is the core meaning that identifies the action.

For some verbs, the stem never changes regardless of the form.

For others, only the last sound of the stem changes in certain verb forms, and it does so in predictable ways.

The Verb Ending

The verb ending carries two pieces of information:

- The tense or form of the verb

- The degree of politeness

In “tabemasu”, the ending “masu” tells us this is the polite present/future tense.

Three Pieces of Information in Every Verb

Japanese verbs encode three pieces of information simultaneously:

1. Functional Meaning

For example, this the present/future tense – “eat” or “will eat”:

And this is the past tense: “ate”

The verb form tells us when something happens and what kind of action it represents (potential, progressive, etc.).

2. Politeness Level

For most verb forms, there’s both a polite version and an informal version:

Polite: “tabemasu”

Informal: “taberu”

Both mean “eat” in the present/future tense, but they convey different degrees of politeness. The informal form is sometimes called the “plain form” or “dictionary form” because it’s how verbs appear in dictionaries.

3. Positive or Negative

In English, we add the word “not” to make verbs negative, but the verb itself stays the same. In Japanese, the negative meaning is built directly into the verb form:

Positive (polite): “tabemasu” – “eat/will eat”

Negative (polite): “tabemasen” – “don’t eat/won’t eat”

Positive (informal): “taberu” – “eat/will eat”

Negative (informal): “tabenai” – “don’t eat/won’t eat”

Notice how the verb ending changes to incorporate the negative meaning, while the stem “tabe” remains constant.

Conjugation in Action: A Simple Example

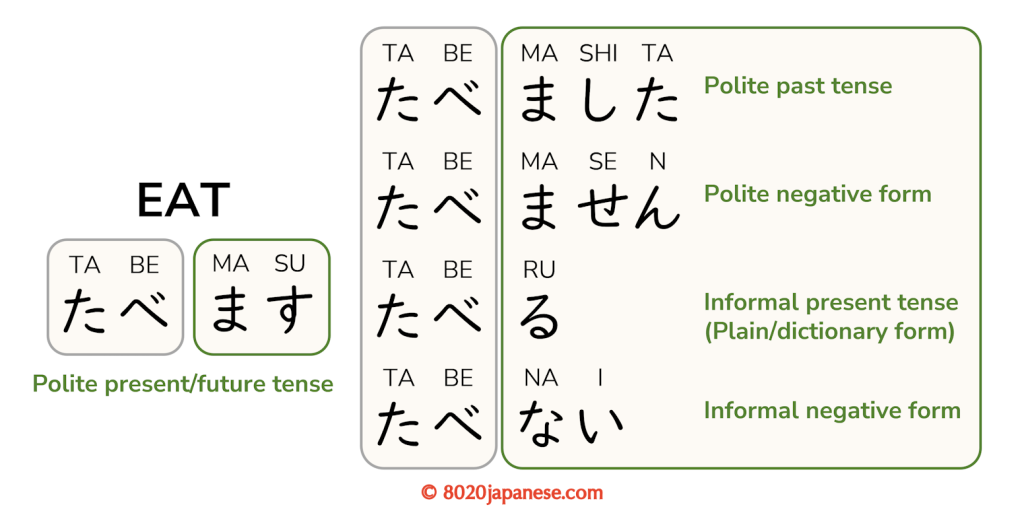

Let’s see how we transform “tabemasu” into different forms by changing only the ending:

Polite present/future tense:

Polite past tense:

Polite negative form:

Informal present/future tense (plain/dictionary form):

Informal negative form:

As you can see, the stem “tabe” stays constant while we change the ending.

This means that to learn a new verb tense or form, you only need to learn ONE ending and it can be applied to all verbs. The only other thing to worry about is whether or not the verb stem needs to change, and if so, how. Let’s look at that now!

When Verb Stems Change: The Predictable Pattern

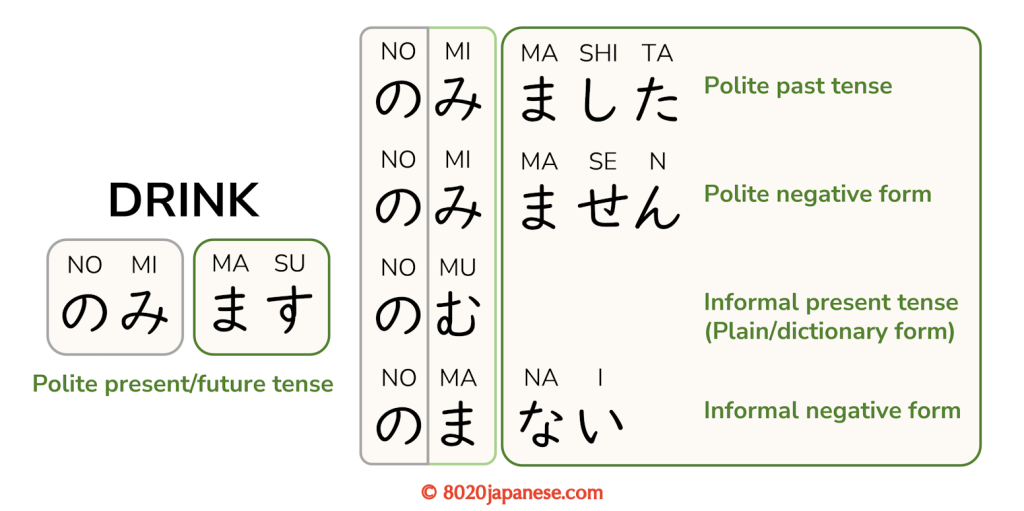

Not all verbs have unchanging stems. Let’s look at “nomimasu”, meaning “drink.”

In the main polite tenses, the stem stays the same:

Polite present/future tense:

Polite past tense:

Polite negative form:

But in informal forms, as well as several others, the last sound of the stem changes:

Informal present/future tense (plain/dictionary form):

→ “mi” changes to “mu”

Informal negative form:

→ “mi” changes to “ma”

Notice that “mi”, “mu”, and “ma” all come from the same line of the Japanese syllabary (the “ma-line”). The stem changes follow recognizable patterns based on syllabary structure. As I said – very logical!

The important thing to remember is that even when stems change, they do so predictably, so you only need to learn the pattern, not memorize a whole bunch of individual exceptions.

The result is that Japanese verb tenses and forms are relatively simple to learn.

Key Takeaways

Japanese verbs consist of two parts:

- The verb stem identifies the action (and mostly stays constant)

- The verb ending indicates tense/form and politeness level

Three pieces of information are encoded in every verb:

- Functional meaning (tense, form, mood)

- Politeness level (polite or informal)

- Positive or negative

The pattern is consistent:

- Polite forms keep the same stem across all variations

- In other forms, the last sound of the stem may change, but in a predictable way

- The same endings apply to all verbs in the same form

Next Steps in Your Japanese Journey

This lesson gives you the structural foundation for understanding Japanese verbs. The next step is learning when to use each form and how to apply them in real sentences.

In my 80/20 Japanese: Foundations course, we build on this foundation systematically, starting with the safest and most practical verb forms (the polite forms) before moving to informal speech and more complex constructions. By focusing on the 20% of grammar that covers 80% of usage, you’ll develop natural, confident Japanese without getting lost in unnecessary details.

Ready to master Japanese verbs the logical way? Explore more free lessons on my blog, or check out the full course to accelerate your learning with the complete system.

Have questions about verb structure? Drop them in the comments below! And if this explanation helped clarify things, share it with a fellow Japanese learner who might be struggling with conjugation.